FDA Antimicrobial Resistance Guidelines Fail to Address Root Causes

Last December, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published two controversial documents on its website: Guidance 213 and the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD). The guidelines stirred a firestorm of protests from public health offiicials who argue that the guidelines are too weak to prevent the continuing growth of antibiotic resistant germs.

Intended to (1) curb the use of medically important antimicrobials (i.e., important to human medicine) for fattening livestock, and (2) increase veterinary control over their therapeutic uses (such as treating, controlling, or preventing disease), the two documents contain guidelines that, if voluntarily accepted, would require veterinary drug manufacturers to make some important labeling changes.

So what's the problem the FDA is trying to solve?

Medically important antimicrobials, which include antibiotics as well as antifungals and antivirals, refer to powerful drugs used in animal agriculture and human medicine alike. By routinely administering antimicrobials in low doses via their livestock's feed and water, farmers can artificially fatten their animals while preventing certain illnesses and infections brought on by unsanitary living conditions. But they also perpetuate a vicious cycle that creates antibiotic and antimicrobial resistance and allows it to spread from farm to table.

This has led to a situation, as stated by Dr. Joseph Mercola, that "it's now clear that we are facing the perfect storm to take us back to the pre-antibiotic age, when some of the most important advances in modern medicine – intensive care, organ transplants, care for premature babies, surgeries and even treatment for many common bacterial infections – will no longer be possible."

As documented by the Centers for Disease Control antibiotic-resistant bacteria infect more than two million Americans every year, causing at least 23,000 deaths. Even more die from complications related to the infections, and the numbers victims are steadily growing. The strains of bacteria themselves are becoming more powerful, creating "super-bugs" and they are evolving rapidly thanks to the overuse and impropriate use of antibiotics.

Even before 1977, when the FDA issued a warning that the farming industry's overuse of penicillin and tetracycline would create a dangerous strain of antibiotic resistance, the agency's attempts to control the problem have proven unsuccessful – not to mention unpopular with the farming industry. But the FDA has returned to the offense, insisting that current agricultural practices contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance in both humans and animals and may eventually render crucial drugs ineffective in the realm of human medicine. (See the official statement here.)

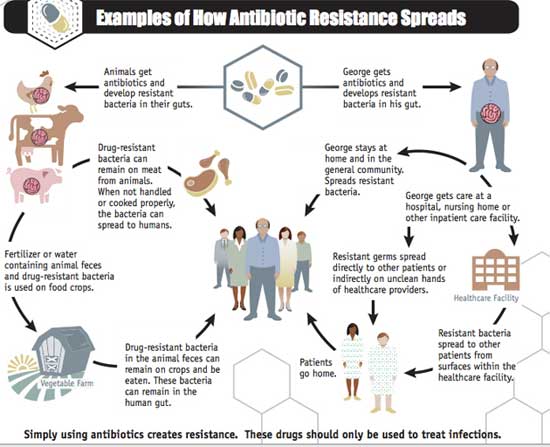

(The chart below, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in its report Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013, illustrates how antimicrobial resistance spreads from farms to human communities. In terms of agriculture, the problem is mainly perpetuated through “factory farms,” or Animal Feeding Operations (AFOs) and especially through Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)).

Antimicrobial resistance threatens modern medicine. Source-CDC

Antimicrobial resistance threatens modern medicine. Source-CDC

The FDA's solution? Require animal drug manufacturers to revise the FDA-approved use conditions on the labeling for antimicrobial drugs that are considered medically important. Also,

[the plan] calls for changing the current over-the-counter (OTC) status to bring the remaining appropriate therapeutic uses under veterinary oversight. Once a manufacturer voluntarily makes these changes, its medically important antimicrobial drugs can no longer be used for production purposes [i.e., growth promotion], and their use to treat, control, or prevent disease in animals will require veterinary oversight.

Although the guidelines are voluntary, the terms become binding once accepted. So far, twenty-five out of twenty-six of the major animal drug manufacturers have complied with the FDA's request. Which, on the face of it, is mighty good news. Afterall, 80% of all antibiotics in the United States are administered to livestock – usually for growth promotion or for preventing sickness. Under the new guidelines, the farming industry would have to implement the following changes over the course of three years:

- no more routinely administered micro-doses that fatten animals (but create antibiotic resistance)

- no more farmers administering antibiotics to entire herds or flocks through feed and water

- licensed veterinarians would oversee the administration of all medically important antimicrobials on farms

“It is important for consumers to know that within three years, all uses of medically important antibiotics in animal agriculture will be only for therapeutic, or targeted, purposes under the supervision of a licensed veterinarian,” the Animal Health Institute (AHI) clarified in an official statement. “We strongly support responsible use of antibiotic medicines and the involvement of a veterinarian whenever antibiotics are administered to food producing animals.”

A more critical point of view....

Despite the good intentions, Guidance 213 and VFD have attracted a wide range of critics – from Senator Elizabeth Warren to Dr. Joseph Mercola. The new guidelines do not address the underlying causes for the present crisis, critics say, and thus will not be able to change the way that antimicrobials are administered in the farming industry. And how does the FDA plan to enforce its policies? Does it even have the means to track its own rate of success?

Over 80% of antibiotics produced are fed to animals image-e-Magine Art-Flickr

Over 80% of antibiotics produced are fed to animals image-e-Magine Art-Flickr

On its FAQ page, the FDA briefly addresses the two latter questions. Once a company has voluntarily accepted the terms, it is bound by law to uphold them. To do otherwise would be to violate the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. As for data tracking, the FDA currently collects information about antimicrobial resistance related to foodborne illnesses via the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) and is working with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to improve its data collection efforts.

Basically, the FDA is “working on it.”

Which is pretty much what Michael Taylor, deputy food commissioner for the FDA, admitted when he discussed the difficulties involved with policing the guidelines and tracking essential data:

The thing to zero in on is, how do we get the data to verify the remaining uses of these drugs are being disciplined, as our policy says they should be, and limited to use in a very targeted way under veterinary supervision, and to verify there are actually reductions in antimicrobial resistance resulting from this? There are a number of policy issues around our ability to get that data… We think we are on a positive pathway, but there is a lot of work remaining to be done.

… The question about which there is a lot of continued skepticism and concern is, how will we at FDA police the remaining prevention uses and how will we document them to be sure they are disciplined. We are going through a rulemaking to see how far under current law we can push the companies to provide data, and also working with (the US Department of Agriculture)… If we can’t get what we need through those means, we won’t hesitate to flag that there is a legislative need here. We need to leave no stone unturned to get the data to demonstrate that we know what is happening.

According to Warren, the FDA's action is a good first step – but that's all.

“Even with every animal drug company agreeing to comply with the FDA's most recent guidance,” she argued in a hearing by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, “there could still be a lot of antibiotic use in animals that is ostensibly for disease prevention, but is still far more than necessary and will continue increasing resistance.”

According to Steve Roach from Keep Antibiotics Working, the FDA “has done nothing to limit the continued use of antibiotics for routine disease prevention. In terms of dose, duration, and number of animals the drug is being administered to, this type of use can be identical to growth promotion, which the FDA is asking the companies to phase out...Getting the companies to send letters is the easy part, actually reducing antibiotic overuse is the real challenge.”

Keeve Nachman, a scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future (CLF), expressed similar concerns about the new guidelines: “The FDA may care whether companies call it growth promotion or disease prevention, but the bacteria do not. If antibiotics are used in the same ways, they will have the same effects.”

The guidelines may require veterinary drug companies to relabel medically important antimicrobials as by-prescription only instead of over-the-counter...but if a dispute is raised, whose definition of “medically important” will win out? The medical field's, the FDA's, or the factory farms'? (According to many critics, the FDA has a poor track record of handling the animal agriculture industry. Even more suspicious, that industry seems to be on good terms with the new guidelines. Why?) Since the animal agriculture industry has disagreed with the medical profession about these terms previously, it's a legitimate question. (In human medicine, for example, tetracycline is considered vital, but the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) dismisses it as “rarely used” in human medicine).

Animal welfare poses another major concern that the FDA has not addressed – and, in fact, holds the key to a vicious cycle that will continue to perpetuate antimicrobial resistance unless changes are made that would shake the agricultural industry to its core.

In the New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, one 2010 study details the atrocious living conditions of animals raised on factory farms (AFOs and CAFOs, which supply the your supermarket with the majority of its meat products). Because the economic model of factory farming relies on “plumping up the greatest number of animals to slaughter-weight as quickly and cheaply as possible,” instead of raising livestock under normal, healthy conditions, the animals are fed cheap but unnatural diets of corn, soy and additives – including animal waste and arsenic.

The animals are packed into warehouses like sardines in a can and, in many or most CAFOs, “never experience sunshine, grass, trees, fresh air, unfettered movement, sex, or many other things that make up most of what we think of the ordinary pattern of life on earth.” Instead, the emotional distress caused by such close confinement and inability to express natural behaviors (such as cows grazing, pigs digging in dirt or straw, and chickens nesting, dust bathing, or foraging) in turn provokes unnaturally violent behavior that pasture-raised animals do not exhibit.

Chickens kept inside CAFO battery cages Source-Wikimedia Commons

Chickens kept inside CAFO battery cages Source-Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, close confinement creates an extremely unsanitary environment where vast amounts of highly toxic animal waste pollute the premises, spreading bacteria and disease everywhere. (In fact, a single dairy farm with 2,500 cows can generate the same amount of waste a city of 411,000 people, and a 500,000 Smithfield Foods hog farm generates more than enough feces and urine to fill four Yankee Stadiums.) According to the study, 10% overall, 4% of cattle, 12% of turkeys, 14% of pigs, and up to 28% of chickens on factory farms die of illness or injury caused by close confinement. Small wonder that such animals are routinely dosed with antibiotics in their feed and water – how else would they survive? These environments are “breeding grounds for bacteria, viruses, and fungi to grow and spread from one animal to another,” and the combination of “intense confinement, stress, poor nutrition, and the noxious environment” greatly reduce the animals' health and compromise their immune systems. For the sake of increased quantity and efficiency, these factory-farmed animals are condemned to lives “full of physical pain and mental suffering.”

In a press release criticizing the FDA, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) made the point that approximately “80 percent of the antibiotics sold in the U.S. are bought to make factory farmed animals […] withstand stressful and unhealthy conditions.” Were the agricultural industry to suddenly abandon this practice, what would happen to the animals? Ironically, the antibiotics create a health hazard for factory-farmed animals (and humans alike), but are necessary to keep the livestock relatively safe from illness and infection. Given the circumstances, it seems unlikely that the FDA would try to prevent AFOs and CAFOs from administering the same routine micro-dosed antibiotics to their livestock as they always have, with or without the oversight of a veterinarian.

The system itself is what needs to change. Dr. Raymond Tarpley, a large animal vet and onetime professor at Texas A&M, confirmed this view. “If you address animal welfare and take care of the animals properly so that natural behaviors are accommodated as possible,” he argued, “you'll decrease stress” and allow the animals to develop immune systems that do not “require the crutch of the antibiotics.” This would break the vicious cycle of antimicrobials spreading antimicrobial resistance and perpetuating the need for administering more drugs – but it would force factory farmers to resort to other, more expensive and less cost-effective methods to protect livestock from an unhealthy environment. It would involve creating a new environment altogether (“enlarging barns, cutting down on crowding, and delaying weaning so that immune systems have more time to develop,” for example).

A medical crisis looms large...

The threat of antimicrobial resistance to human health has steadily gained recognition in the medical world. And it's becoming harder and harder to deny that this threat is linked to the farming industry.

According to the CDC, 48 million Americans – that's 1 in 6 of everyone you pass by on the street – get sick through foodborne illnesses. 128,000 people per year are hospitalized and approximately 3,000 people die per annum. The cause of these foodborne illnesses? Over 250 types of toxins and pathogens – bacteria, viruses, and parasites – spread by contaminated food and drink.

Most of that food, of course, originates from contaminated meat raised on a farm or crops grown in the fields (often sprayed with manure containing antibiotic-resistant organisms, antibiotics, and resistance genes). If resistance occurs on the farm, it can easily find its way to the supermarket. In 2011, the FDA found that 65% of chicken breasts and 44% of ground beef contained bacteria resistant to tetracycline while 11% of pork chops contained bacteria resistant to multiple types of drugs. But groundwater, dust, and flies can also transport resistant bacteria into human communities. Lest opponents argue that the connection between factory farms, antibiotic resistance, and human health is a tenuous one, recent studies do provide examples:

The increasing populations of swine raised in densely populated CAFOs and exposed to antibiotics presents opportunities for drug-resistant pathogens to be transmitted among human populations. Our study indicates that residential proximity to large numbers of swine in CAFOs in Iowa is associated with increased risk of MRSA colonization.

Of course, antimicrobial resistance does originate from other sources as well – most notably, our medical system. According to Eric Lander, co-chair for PCAST (President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology), a “bare minimum, very conservative” estimate of 23,000 deaths occur per year due to antibiotic-resistant organisms, and the rate of the development of antibiotic resistance is increasing. Lander lamented the lack of stewardship of antibiotics in both healthcare and agricultural settings. In terms of percentages, he said, it is impossible to know how much of the problem is due to the medical system and how much is due to the agricultural industry, but both industries are very much to blame.

Hog confinement in a factory farm-Image Source-Wikimedia CommonsAnd while most people view antimicrobial resistance as a problem “that happens somewhere else, to other medical practices, to other farms, other patients, and other people,” Thomas Frieden, director of the CDC, reminds us of the truth: “[A]ntimicrobial resistance is happening here, in every community, in every health care facility, in medical practices throughout the country” (emphases added). And unfortunately, it doesn't take much for antimicrobial resistance to begin developing. It doesn't take very long, either.

Hog confinement in a factory farm-Image Source-Wikimedia CommonsAnd while most people view antimicrobial resistance as a problem “that happens somewhere else, to other medical practices, to other farms, other patients, and other people,” Thomas Frieden, director of the CDC, reminds us of the truth: “[A]ntimicrobial resistance is happening here, in every community, in every health care facility, in medical practices throughout the country” (emphases added). And unfortunately, it doesn't take much for antimicrobial resistance to begin developing. It doesn't take very long, either.

When Alexander Fleming accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1945 for his discovery of penicillin nearly two decades earlier, he warned that it “is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them...There is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to none-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.”

Which is exactly what is happens when farmers routinely administer low doses of antimicrobials to their livestock. In the world of human medicine, it can happen whenever a patient does not finish a prescription or is given the wrong dose. According to the CDC, “research has shown that as much as 50% of the time, antibiotics are prescribed when they are not needed or they are misused …. This inappropriate use of antibiotics unnecessarily promotes antibiotic resistance.” The inevitable consequence, of course, is that many medically important antibiotics are losing their usefulness to human medicine:

Fleming’s prediction was correct. Penicillin-resistant staph emerged in 1940, while the drug was still being given to only a few patients. Tetracycline was introduced in 1950, and tetracycline-resistant Shigella emerged in 1959; erythromycin came on the market in 1953, and erythromycin-resistant strep appeared in 1968. As antibiotics became more affordable and their use increased, bacteria developed defenses more quickly. Methicillin arrived in 1960 and methicillin resistance in 1962; levofloxacin in 1996 and the first resistant cases the same year; linezolid in 2000 and resistance to it in 2001; daptomycin in 2003 and the first signs of resistance in 2004.

Antimicrobials - especially antibiotics – have made modern medicine possible. Ever since 1940, when our medical world began to treat serious infections with antibiotics, these drugs have saved countless lives and have become an indispensable tool for a growing number of medical operations and other medical uses. But perhaps we have relied on them too heavily. No antibiotic can prevent bacteria from developing a resistance to it, “[and] the more the antibiotics are used, the more quickly bacteria develop [and spread] resistance”: “If we're not careful, the medicine chest will be empty when we go there, to look for a live-saving antibiotic for something with a deadly infection,” Frieden warned in the report.

Without urgent action now, more patients will be thrust back to a time before we had effective drugs. We talk about a pre-antibiotic era and an antibiotic era. If we're not careful, we will soon be in a post antibiotic era. And, in fact, for some patients and some microbes, we are already there. Losing effective treatment will not only undermine our ability to fight routine infections, but also have serious complications, serious implications, for people who have other medical problems. For example, things like joint replacements and organ transplants, cancer chemotherapy and diabetes treatment, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. All of these are dependent on our ability to fight infections that may be exacerbated by the treatments of these conditions. And if we lose our antibiotics, we'll lose the ability to do that effectively. [Emphasis added]

What other benefits might we lose to antimicrobial resistance? Maryn McKenna continues the list:

- ability to treat infectious disease

- ability to treat cancer

- ability to transplant organs

- any treatment that relies on a permanent port into the bloodstream (kidney dialysis, etc)

- Any major open-cavity surgery (heart, lung, abdomen surgeries)

- any surgery on a part of the body that harbors bacteria (guts, bladder, genitals)

- implantable devices: new knees, heart valves, etc.

- cosmetic plastic surgery

- liposuction

- tattoos

- safety of modern childbirth

- a good portion of our modern food supply (meat, produce, etc)

Clearly, this is not a minor issue. A medical crisis looms large; if the situation is not handled properly, the storm clouds will break. While the FDA is right to recognize the seriousness of the problem, and is attempting to work with the a major source of the problem, it needs to dig deeper down to address the root cause of animal welfare and the environment that makes factory farming possible. In the meantime, let's hope their data-tracking systems improve, and that they will be able to enforce their guidelines and implement the changes necessary for taking the next step forward.

- Tags:

- Alexander Fleming

- American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA)

- animal agriculture

- animal cruelty

- animal feeding operations (AFOs)

- animal welfare

- antibiotic resistance

- Antibiotics

- antimicrobial resistance

- antimicrobials

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs)

- confinement

- contaminated meat

- data collection

- data tracking

- disease prevention

- Elizabeth Warren

- Eric Lander

- factory farms

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- food production

- foodborne illnesses

- growth promotion

- Guidance for Industry 213

- healthcare

- Joseph Mercola

- Keeve Nachman

- Maryn McKenna

- Michael Taylor

- modern medicine

- National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS)

- President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST)

- Raymond Tarpley

- Steve Roach

- Thomas Frieden

- unsanitary conditions

- Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD)

- veterinary oversight

- Login to post comments

Comments

Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases physicians, public health experts and others are greatly concerned about non-judicious uses of antibiotics in agriculture and particularly in food animals. The relationship between antibiotic-resistant infections in humans and antibiotic use in agriculture is complex, but well-documented. Many farmers have made it common practice to give animals antibiotics to ensure they are healthy, even if the animal would not normally be healthy. The Food and Drug Administration, however, will be limiting some of this practice in order to keep human antibiotic resistance from growing.

A large and compelling body

A large and compelling body of scientific evidence demonstrates that antibiotic use in agriculture contributes to the emergence of resistant bacteria and their spread to humans. IDSA is working to eliminate inappropriate uses of antibiotics in food animals and other aspects of agriculture and aquaculture.

Taking action against

Taking action against antimicrobial resistance is appreciable. Because, it's very dangerous for human health. It's really a matter disappoint when the action goes far in vain. Firstly, FDA should be well collaborated and prepare a plan and then apply it on real scenarios. Finding newer tricks to figure out the root cause would be helpful for quick and effective solution.