Halamka Says We Can and Must Improve Healthcare Management

John D. Halamka, M.D.As a physician and CIO, I’m quick to spot inefficiencies in healthcare workflow. More importantly, as the care navigator for my family, I have extensive firsthand experience with patient facing processes.

John D. Halamka, M.D.As a physician and CIO, I’m quick to spot inefficiencies in healthcare workflow. More importantly, as the care navigator for my family, I have extensive firsthand experience with patient facing processes.

My wife’s cancer treatment, my father’s end of life care, and my own recent primary hypertension diagnosis taught me how we can do better.

Last week, when my wife received a rejection in coverage letter from Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark, it highlighted the imperative we have to improve care management workflow in the US.

Since completing her estrogen positive, progesterone positive, HER2 negative breast cancer treatment in 2012 (chemotherapy, surgery, radiation), she’s been maintained on depot lupron and tamoxifen to suppress estrogen. After three years on a protocol of 22.5mg of lupron every 3 months, her insurer and pharmacy benefits manager decided that 11.25mg was an equally effective dose and sent her a letter telling her they would no longer cover 22.5mg dosing.

Here’s the actual letter she received.

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "HPHC has not made arbitrary decisions on the Lupron dosage for breast cancer, nor with any other policies for that matter. Rather, HPHC has implemented an IV drug management program using the best peer review medical evidence and professional societies guidelines. In the case of oncology drugs, the program has adopted recommendation from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), a not-for-profit alliance of 27 leading cancer centers devoted to patient care, research, and education. In Boston, MGH and DF/BW are NCCN member institutions."

Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark was very collaborative in discussing next steps, and I was eager to bring them into the conversation.

There are 5 issues with the letter.

1. Her oncologist was unaware that Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark had such a program. HPHC included an article about the new program in their newsletter and sent email to those clinicians who were likely to be affected. Although a good attempt, those communication modalities did not reach my wife’s oncologist.

2. The rule is stated in a confusing way as "prescriptions for 3.75 mg". How does this relate to my wife’s 22.5mg treatment?

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "Per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, Lupron 22.5mg is indicated for prostate cancer and not breast cancer. For breast cancer, the guidelines recommend 3.75mg monthly or 11.25mg every three months (a 50% reduction in Kathy’s dose). "

Kathy would have preferred something like ‘national guidelines recommend a 50% reduction in dose to achieve the same outcome with fewer side effects’.

3. Although Kathy’s oncologist is aware of the NCCN guideline, he believes the evidence supporting the guideline is scant (a single paper from 1990), so based on his experience with hundreds of successful cancer patients, he prefers 22.5mg.

Kathy’s oncologist writes: "I think the Dowsett paper—and Mitch is great and a colleague—is a very small 1990 study using 2 doses of lupron in women with metastatic breast cancer. Not very compelling evidence, especially when translated to a different clinical setting. That being said, no one knows for sure what dose is adequate and it probably isn’t the same for all women. In a treat for cure setting, we would rather err on the side of more drug than may be needed in that individual (as it is quite safe) rather than fail to suppress and therefore diminish effectiveness of planned treatment. The absence of menses is not evidence of ovarian suppression since about 20% of women with no periods still have ovarian function."

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "The NCCN guidelines support the 3.75mg IV monthly injections because the 22.5mg depots every three months’ injections do not reliably suppress estrogen in all women, which is the whole point of the treatment There are numerous examples of individual physicians who make assumptions based on their observations and individual experience. In many cases, however, those observations have not been confirmed by future clinical trials and may reflect unconscious bias on the part of the treating physician. Kathy’s oncologist doesn’t appear to have published his observations in a peer review journalwith hundreds of patients using the off-label dose of Lupron 22.5mg every three months. In addition, if he feels strongly that the 22.5 mg is the preferred dose, he has a professional obligation to suggest modifications of the NCCN guidelines. We don’t know if he has made an attempt to modify the NCCN guidelines."

I completely understand Harvard Pilgrim’s motivation to implement a guideline, and NCCN is what is available. The central issue with the letter is not the guidelines themselves, but how the program was implemented before patient/provider educational and workflow concerns had been addressed.

4. The patient is being asked to manage something they lack the expertise to do - bringing together payer medical management and provider caregivers to discuss a medication dose.

Harvard Pilgrim’s writes: "There are many avenues for appeal and the patient is not being asked to manage the process. The contracted provider, who is credentialed by HPHC and who has signed a contract with HPHC, has a responsibility to manage the process by calling the plan or the delegated entity or both, whenever he/she disagree with the initial determination. In addition, the patient and provider can submit a formal appeal requesting an external specialist’s review of the case. In a similar different case to Kathy’s, the external expert in the same specialty (not chosen by the plan), agreed with the NCCN guidelines and HPHC. The match specialist is a board-certified oncologist working at an academic medical center in Pennsylvania. Finally, if the denial is upheld on first level appeal, the patient and physician can appeal to the State. The process is fair and equitable and attempts to balance self-interest and autonomy with common interest and use of evidence-based medicine with the ultimate goal of managing limited resources and continuously increasing care cost in the New England market."

I leave the readers to judge for themselves if the patient is being asked to manage a process.

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "There are many avenues of appeal if the physician does not agree and the physician has a professional responsibility to act as the patient advocate, and to explain to the health plan medical director the rational for supporting a treatment that is not recognized by any of the compendia (Micromedix, Facts and Comparison) and NCCN guidelines."

5. The decision was made without consulting Kathy’s clinical record or cancer treatment protocol. I’ve recently co-authored a book about precision medicine which highlights the need to combine evidence, patient preference, clinical history, genomics, and the experience of other patients to select the right treatments. We all should be working toward that future.

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "While Dr. Halamka is correct that we do not have access to clinical records, in order to ensure that we have relevant information, we ask the treating physician to provide it to us so that we can utilize it in decision-making Participating physicians are asked to fill out a form (designed by the State) and include information relevant to the case. In addition, physicians have the opportunity to call the health plan or the delegated entity and initiate a peer to peer discussion. During the peer to peer discussion, the patient physician has the opportunity to provide the clinical rationale as of why the plan should cover a treatment that deviates from FDA, or other professional guidelines."

Again, I leave it to the readers to decide how a clinician is going to follow that workflow while having 12 minutes to see each patient, comply with Meaningful Use-imposed EHR burdens, be empathic, make eye contact, and never commit malpractice.

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "A physician should never abdicate his/her ethical obligation to support his/her patients in the entire process of care. Many practices delegate certain non-direct patient care functions to other members of the clinical team. However, the physician must always act as patient advocate. In this case, patient advocacy means picking up the phone and having a discussion with a medical director at the Health Plan. To their credit, many physicians do call the plan and interact with the medical directors."

Sometimes in the healthcare industry we implement changes before policy, technology, and culture are ready. For example, healthcare regulations required encryption of mobile devices before any laptop or phone operating system supported encryption. Meaningful Use tried to accelerate interoperability before we had an electronic provider directory, a nationwide patient matching strategy, or a framework for consistent privacy policy among states. Care management disconnected from clinical workflow has the same problem.

Here are three alternatives which would markedly improve the patient experience

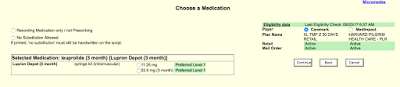

1. The actual Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark formulary is shown below from the e-prescribing function inside my wife’s EHR. I did an eligibility check demonstrating that both Caremark and Medimpact pharmacy benefits mangers consider 22.5 mg a preferred level 1 medication for 3 month administration without any designation that there is a care management decision support rule to consider. Given that Kathy is female and therefore unlikely to have prostate cancer, there is no reason to offer the 22.5mg option. Imagine if during e-prescribing, the rule was displayed/enforced so that 22.5mg wasn’t considered preferred level 1, resulting in a patient/doctor conversation before the medication is ordered.

Harvard Pilgrim writes: "The PBM or Health plan formulary is not designed as a drug management tool. The preferred product designation in the formulary is a cost management tool. The formulary must list all the available dosages so that even an off-label dosage can be dispensed, like in Kathy’s case, as an exception to the medical policy after discussion with the patient physician. Clearly, there is an opportunity to further educate providers on the difference between utilization management and formularies."

2. As a country, we need to finalize the standards for pre-authorization with clinical attachments. Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark could create a rule as part of the pre-authorization workflow. Appropriate clinical documentation would be required before the pre-authorization is approved, again resulting in a patient/doctor conversation before the medication is ordered. Alternatively, the emerging Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) Clinical Decision Support Hooks specifications will enable EHRs to query cloud hosted clinical rules and display precision medicine information to the provider at the point of care.

3. The letter from Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark, could be revised as follows

'Harvard Pilgrim, Caremark, and your care team work together to keep you healthy. We’re constantly reviewing evidence about the best possible treatments. Based on recent research, it appears you are receiving too high a dose of Depot Lupron, which could cause unwanted side effects. We will contact your doctor and have a discussion about the protocol you are on, taking into account your individual medical history, to collaboratively decide on the best dose for you. We just wanted you to know that in case your prescription changes, it’s all because of new knowledge and experts working together.'

I applaud the intent of care management as a way to improve quality and reduce costs. However, just as with Meaningful Use, I think the letter is a good example of trying to do too much too soon.

I’m not asking that Harvard Pilgrim and Caremark eliminate their care management program. I am asking that they realize the deficiencies of launching a program before the education and workflow redesign efforts were mature, putting the patient in the middle of what should be a payer-provider conversation. The tools to implement that payer-provider conversation don’t yet exist, but soon will and HPHC/Caremark could start by modifying their formularies to offer preferred choices in existing e-prescribing workflows.

As John Kotter taught us in his change management work, we need to follow a process, beginning with a sense of urgency in order to make lasting change. We know that the US must reduce total medical expense while maintaining quality and optimizing outcomes if we are to have a sustainable economic future. Care management based on evidence is the right thing to do. Now we need to work together so that payer systems, decision support rules, and EHRs have a closed loop workflow for all involved. I’m happy to serve on the guiding coalition, along with my colleagues at HPHC, to make this happen.

| Halamka Says We Can Improve Healthcare Management was authored by Dr. John D. Halamka and published in his blog, Life as a Healthcare CIO. It is reprinted by Open Health News under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. The original post can be found here. |

- Tags:

- breast cancer

- cancer treatment

- cancer treatment protocol

- care management workflow

- chemotherapy

- clinical decision support

- clinical workflow

- cloud hosting

- data encryption

- decision-making in healthcare

- depot lupron

- e-Prescribing

- electronic health records (EHRs)

- electronic provider directory

- Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)

- Harvard Pilgrim/Caremark

- healthcare communications

- healthcare workflow inefficiencies

- Hooks specifications

- interoperability

- IV drug management program

- John D. Halamka

- John Kotter

- Meaningful Use-imposed EHR burdens

- Medimpact

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)

- nationwide patient matching strategy

- patient advocacy

- patient facing processes

- payer medical management

- precision medicine

- provider caregivers

- tamoxifen

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- Login to post comments