The Big Get Bigger, Until They Don't

Kim BellardYou may have missed it, but the Open Markets Institute released a report on what it calls "America's Concentration Crisis." The report begins bluntly: "Monopoly power is all around us: as consumers, business owners, employees, entrepreneurs, and citizens." As David Leonhardt wrote in his op-ed about the report, "The federal government, under presidents of both parties, has largely surrendered to monopoly power."

Kim BellardYou may have missed it, but the Open Markets Institute released a report on what it calls "America's Concentration Crisis." The report begins bluntly: "Monopoly power is all around us: as consumers, business owners, employees, entrepreneurs, and citizens." As David Leonhardt wrote in his op-ed about the report, "The federal government, under presidents of both parties, has largely surrendered to monopoly power."

Their associated data set details market concentration within 32 industries, several of which are health related. For example, in electronic health record systems, the top 3 firms account for 58% of the market, whereas in pharmacies/drugstores, the top 3 control 67% (and the top 2 alone have 61% share).

This shouldn't come as a surprise by anyone who pays even minimal attention to healthcare, yet here we are. Perhaps due to the available data, Open Markets Institute did not look at hospitals, physicians, payors, or pharma, but a few months ago, Lindsay Resnick, writing in Becker's Healthcare, warned that we should "get ready for a future of rampant healthcare consolidation." He cited the following:

- Five for-profit insurers now control 43% of the market.

- More than 60% of community hospitals belong to a health system

- Less than half of physicians own part of a private practice.

- Vertical integration mergers and acquisition deals topped $175 billion in 2017.

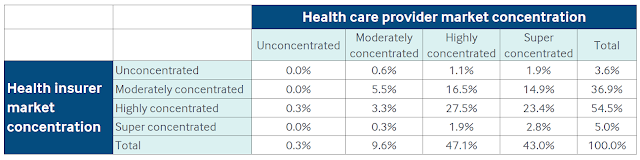

Even more telling, earlier this year the Commonwealth Fund released a report about market concentration of healthcare providers and health insurers, and found that 43% of markets were "super concentrated" for providers and another 47% were "highly concentrated." For insurers, 55% of markets were highly concentrated and 37% were moderately concentrated.

The argument is always that such consolidation leads to great efficiencies and more ability to reduce unnecessary care, but as far as I know, the research to support such claims does not exist. To the contrary, study after study has found that consolidation almost always to higher prices and increased spending.

The New York Times recently commissioned its own study on the matter, and found that: "The mergers have essentially banished competition and raised prices for hospital admissions in most cases." In the 25 markets it studied, prices went up from 11% to 54%. As one expert told them, "The puzzling part for many of us in the state is why anyone would allow these oligopolies to form."

Mr. Leonhardt and the Open Markets Institute could explain it.

Mr. Leonhardt attributes both income stagnation and a decline in entrepreneurship at least in part to what he calls this "corporate gigantism," and Dave Chase, among others, has been preaching for years that, specifically, out-of-control health care costs have been robbing workers of wages for years.

We don't have an Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook or Microsoft in healthcare -- yet -- but, left unchecked, it's only a matter of time before local/regional monopolies become national ones.

It would be easy to get discouraged about this trend, but the ever-optimistic John Nostra, writing in Psychology Today, points out: "Giants are meant to die." He cites the work of Professor Mark Perry, who looked at the Fortune 500 in 1955 and again in 2017, and found that 88% of the ones in 1955 did not make the latter list. Some had gone bankrupt, some had merged/been acquired, and some were just were no longer big enough to qualify. Professor Perry refers to this as "Schumpeterian creative destruction."

Professor Perry sees this as a "positive sign of the dynamism and innovation that characterizes a vibrant consumer-oriented market economy, and that dynamic turnover is speeding up in today's hyper-competitive global economy." Mr. Nostra is similarly encouraged, noting: "The early movers in a marketplace can often become the dominant player, but commonly, they are also the ones who stumble."

It wouldn't seem that time-honored institutions like hospitals, physicians, pharmaceutical companies or health insurers are "early movers," but it may just be a matter of perspective. It may be that our medical model of "health care" is the early mover, and will be replaced by other models that do not value those as highly.

As I've written previously, healthcare's "monoculture of thought" limits its ability to come up with truly new ideas and approaches, thus creating opportunities for outsiders.

Take what's happening in banking. Traditional banking is a huge industry, also time-honored and increasingly concentrated, but it is being challenged by "neo-banks" -- typically digital only enterprises without a bank charter. Accenture says 19% of financial institutions in the U.S. are considered new entrants, largely what they term "digital disruptors." The New York Times reports that U.S. neobanks received four times as much venture capital so far in 2018 as they did all last year, and ten times as much as in 2015. Chime, for example, has 2 million accounts and is adding more customers per month than Wells Fargo or Citibank. Neobanks in other countries, including Australia, Britain and China, are moving even faster.

World Finance asserts that the 2008 global financial crisis led to a wave of anger towards, and lack of trust in, traditional banks that has created the opportunity for neobanks. Even so, though, "they will need to offer a positive alternative of their own that is more convenient, more secure and cheaper than what is currently available."

I don't know what healthcare's "neobanks" are going to be (for that matter, the financial services industry isn't yet sure what its own neobanks are really going to be). Perhaps they will be AI personal health assistants or 3D printed-at-home prescription drugs. Perhaps they will be something someone is still sketching out the idea for. Perhaps we won't even recognize them as being such at first.

If consumers' anger towards and lack of trust in an industry creates opportunities for outsiders, then healthcare certainly is ripe, perhaps even more than financial services. We're going to see more market consolidation in healthcare before we see effective challenges to it...but we will see them. Even giants die.

Healthcare does have a concentration crisis, but that creates opportunities for the right challengers. Who will they be?

| The Big Get Bigger, Until They Don't was authored by Kim Bellard and first published in his blog, From a Different Perspective.... It is reprinted by Open Health News with permission from the author. The original post can be found here. |

- Tags:

- Accenture

- Commonwealth Fund

- corporate gigantism

- David Leonhardt

- digital disruptors

- electronic health record systems (EHRs)

- health care costs

- healthcare consolidation

- John Nostra

- Kim Bellard

- Lindsay Resnick

- Mark Perry

- monoculture of thought

- monopoly power

- neo-banks

- Open Markets Institute

- Schumpeterian creative destruction

- vertical integration mergers

- World Finance

- writing in Becker's Healthcare

- Login to post comments