2017 Prediction: Some "Oops" Ahead

Kim BellardPredictions for 2017 are everywhere this time of year, and it is no wonder. There are so many technological advances, in health care and elsewhere, and a seemingly endless appetite for them. We all want the latest and greatest gadgets, we all want the most modern treatments, we all have come to increasingly rely on technology, and we all -- mostly -- see an even brighter technological future ahead.

Kim BellardPredictions for 2017 are everywhere this time of year, and it is no wonder. There are so many technological advances, in health care and elsewhere, and a seemingly endless appetite for them. We all want the latest and greatest gadgets, we all want the most modern treatments, we all have come to increasingly rely on technology, and we all -- mostly -- see an even brighter technological future ahead.

Here's my meta-prediction: some of the predicted advances won't pan out, some will delight us -- and all will end up surprising us, for better or for worse. Like Father Time and entropy, the law of unintended consequences is ultimately undefeated.

What started me thinking about this was an article in Slate, "Self Driving Cars Will Make Organ Shortages Worse." Self-driving cars are a hot area these days, with auto makers trying to prepare for a future where car ownership lessens in importance and driving services like Uber and Lyft trying to make that happen.

One of the key appeals of self-driving cars is that, well, humans generally are pretty crummy drivers, being prone to distractions, falling asleep, driving while impaired, and so on. Without us, the reasoning goes, there should be a lot fewer accidents and deaths.

That sounds like good news (unless you are in the auto repair business), but, as the Slate article points out, 1 in 5 organ donations come from of victims of car accidents. Stop us from killing ourselves or others on the road, and suddenly a huge problem crops up for those roughly 120,000 people on the organ transplant waiting list.

Talk about unintended consequences.

Well, you might say, that's a good problem to have, and technology will fix it too. After all, soon we'll have artificial organs, even 3D printing them. As big a fan of bionics and 3D as I am, though, somehow I suspect there are some shoes yet to drop with them as well.

An even more worrisome example is gene editing. In a recent post, I likened its potential to magic. Snip a few undesired genes out, substitute some other ones, and we can potentially cure or prevent some important health problems.

Even more startling, the technology can be used to ensure that such edits persist and spread in subsequent generations, potentially changing entire species. This process of changing entire future generations is called "gene drive."

Magic indeed.

The same could be done with say, mosquitoes and the malaria they can carry.

The potential dangers are becoming recognized. The director of national intelligence listed gene drive as a potential weapon of mass destruction, a concern echoed by the National Academy of Science. As Dr. Esvelt said. "My greatest fear is that something terrible will happen before something wonderful happens. It keeps me up at night more than I would like to admit."

Worse yet, the terrible things may not even be deliberate. As another researcher warned Mr. Specter:

But gene drives affect entire communities, not single individuals. And it can be almost impossible to predict the dynamics of any ecosystem, because it is not simply additive. That is exactly why gene drives are so scary.The real danger may be that an overwhelming need in a local area -- e.g., Ebola, AIDS, malaria -- may cause local officials to take chances. As an African public health official told Mr. Specter, "Principles matter to us as much as they do to Americans. But we have been dying for a long time, and you cannot respond to death with principles."

Applying gene edits in such a situation might solve immediate concerns, but with broader implications. Dr. Esvelt put it bluntly: "A release anywhere could be a release everywhere."

Because CRISPR is making the technology much cheaper and much more accessible, how it is used becomes especially important. We don't really want someone in their garage lab inadvertently wiping out all cats, for example. As Dr. Esvelt stressed, "The only way to conduct an experiment that could wipe an entire species from the Earth is with complete transparency,"

That may be a big ask; we're

Mr. Specter himself appears to be cautiously optimistic:

We have engineered the world around us since the beginning of humanity. The real question is not whether we will continue to alter nature for our purposes but how we will do so. Using a mixture of breeding techniques, we have transformed crops, created countless breeds of animals, and converted millions of wooded acres into farmland. Gene drives are different; one insect could affect the future of our species. But it is a difference of power, not of kind.

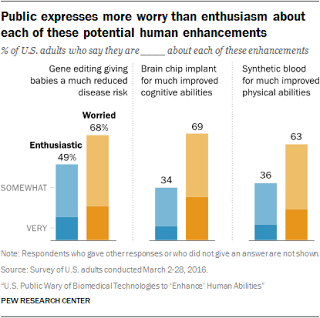

Pew Research Center did a study on using biomedical technologies to enhance human abilities, and found that we are decidedly skeptical. About two-thirds were worried about each of the three specific scenarios -- gene editing, brain implants, and synthetic blood -- but about three-fourths thought that the technologies would end up being used before they were fully tested or understood.

Ironically, respondents were most enthusiastic about gene editing, but only in regards to doing so to give babies a reduced disease risk -- not changing our entire population through a gene drive.

Technology change is going to happen. It will inevitably change our culture and, to some extent, us. We're not very good about not using technology once invented. The question is how we prepare for it. Christopher Mims believes that "the art and science of futuring is fast becoming a necessary skill." It is less about predicting the future than preparing for a variety of futures

As Donald Rumsfeld infamously once said, there are known unknowns and unknown unknowns. We think more about the former than the latter, but that needs to change.

We should be spending as much time thinking about the potential consequences -- good and bad -- of cool new technologies as we do being excited about how cool they seem.

| 2017 Prediction: Some "Oops" Ahead was authored by Kim Bellard and first published in his blog, From a Different Perspective.... It is reprinted by Open Health News with permission from the author. The original post can be found here. |

- Tags:

- 3D printing

- Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

- artificial organs

- brain implants

- Christopher Mims

- clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)

- Ebola

- gene drive

- gene editing

- Kevin Esvelt

- Kim Bellard

- law of unintended consequences

- Lyft

- Lyme disease

- malaria

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

- Michael Specter

- National Academy of Science

- Pew Research Center

- self-driving cars

- synthetic blood

- transparency

- Uber

- Login to post comments